-

American Cities Practice

Creating Neighborhoods of Opportunity through Citywide Initiatives

It’s All Hands on Deck in MemphisNeighborhood Preservation Inc. (NPI) and Knowledge Quest are among 10 Memphis, Tennessee, organizations to be awarded a total of $1.3 million in grants by The Kresge Foundation in a 2017 open call for proposals to boost opportunity for city residents with low incomes.

The open call was one part of a broader acceleration of Kresge investments in Memphis, where the foundation helps support neighborhood nonprofits and citywide community development organizations and intermediaries across sectors. Since 2014, Kresge has contributed $6.6 million ($3 million in social investments and $3.6 million in grants) to spur economic and community development in Memphis. Multiple Kresge teams in a variety of disciplines collaborated to provide the funding.

Chantel Rush, program officer with Kresge’s American Cities Practice, says Memphis illustrates Kresge’s commitment and approach to “place-based work.”

“We seek to serve as a supportive philanthropic partner to Memphis nonprofits, public-sector leaders and local philanthropy,” Rush says. “We support both citywide organizations and those driving positive change in neighborhoods.

Carnes Garden is a community learning garden in the Carnes-Galloway neighborhood of Memphis — a major strategic priority for Neighborhood Preservation Inc. “Our investments recognize the good work underway and increase the access Memphis-based institutions have to national resources.”

Kresge’s work in Memphis exemplifies the ways the foundation works across programs and disciplines, with grantmaking that involves Health, Human Services, Arts & Culture and Education, along with Social Investments, to promote a geography of opportunity in the city.

‘The Secret Sauce’

It has been a 20-year journey for Knowledge Quest, but a short one for founder and Executive Director Marlon Foster. Born and raised in South Memphis, he went to LeMoyne-Owen College. After college, he spurned job offers outside the city because he wanted to start a business in the neighborhood where he grew up.

The result was Knowledge Quest, a youth-centered organization serving some of the most poverty-stricken ZIP codes in Memphis.

Knowledge Quest’s Green Leaf Learning Farm operates as a certified USDA organic farm. “My friends told me I turned into a social worker, but I said I was a social entrepreneur,” he says.

Knowledge Quest has evolved from a few after-school programs to a 3-acre main campus centered on urban agriculture and two off-campus locations with ancillary programs — all in a neighborhood cited five years ago as one of the United States’ most dangerous.

“We have been slow and methodical,” Foster says. “Our most valuable asset is an authentic relationship of trust with the neighborhood. That’s our secret sauce.”

An idea from a teacher “who wanted kids to know where food comes from” led to Knowledge Quest’s emphasis on nutrition and gave birth to the Green Leaf Learning urban micro-farm. It began when Foster offered to cut the grass on an overgrown lot in exchange for permission to plant vegetables there.

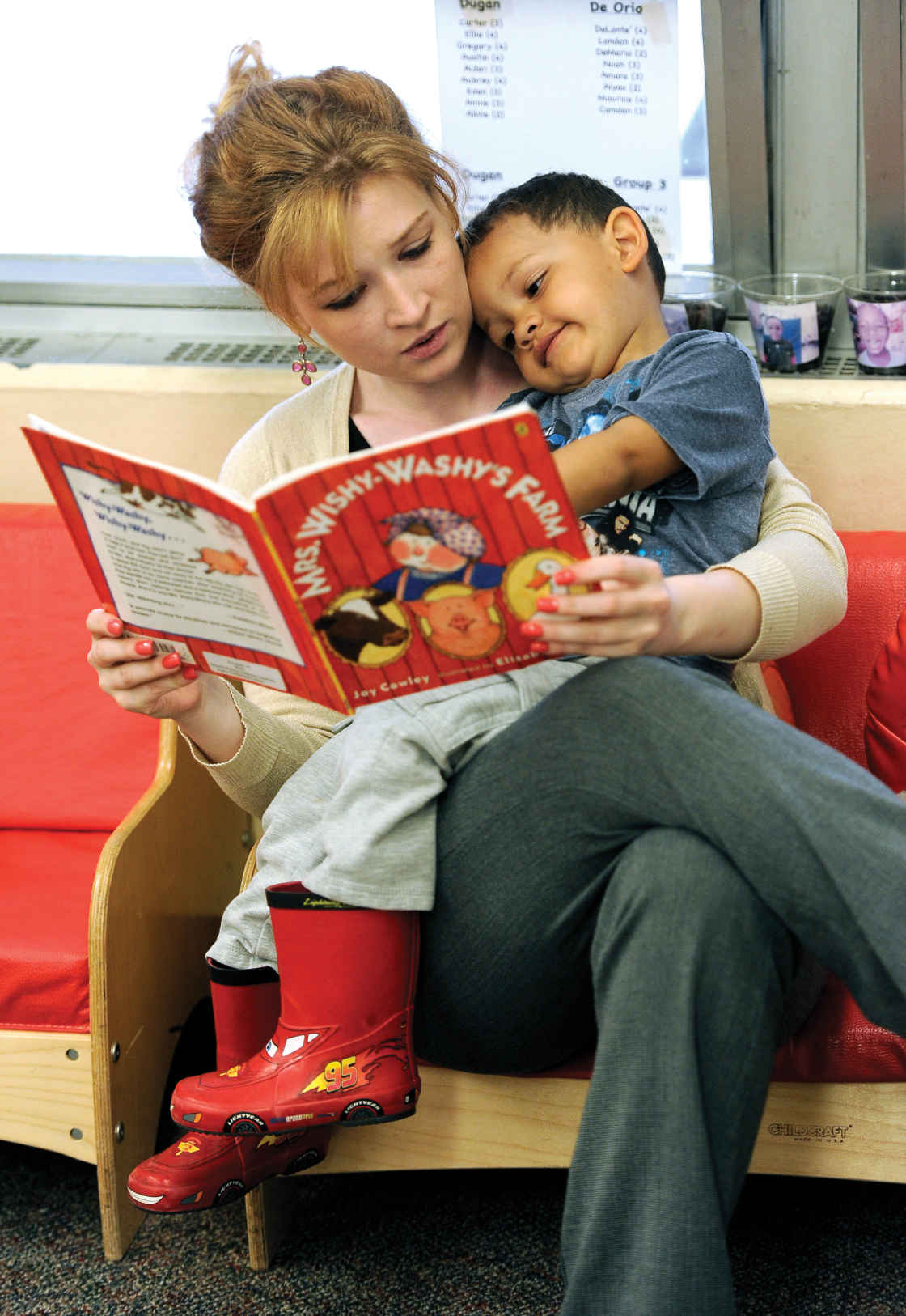

Knowledge Quest teaches students about growing food in ways that build community and increase access to healthy foods. Now owned by Knowledge Quest, that first lot features 44 seedbeds, a pavilion, a compost bin, a climate-controlled greenhouse and a worm farm. Next door, three abandoned buildings are being repurposed; there’s also an orchard nearby.

Changing the Narrative

Meanwhile, Knowledge Quest continues its after-school offerings, a program supporting families at risk of becoming homeless or displaced, a Universal Parenting Place with resources to address behavioral issues early in a child’s development, and the Jay Uiberall Culinary Academy, where high school students train with guest chefs.

“Everything is related to Green Leaf,” Foster says. “We were typecast as a youth development organization, but to me, it was community development, taking our highest and best asset — our children — and building community development around their own development.

Neighborhood Preservation Inc. makes engaging the community a priority in its revitalization efforts. “What I envisioned with Green Leaf was education, housing, economic development, community development and more. It is its own ecosystem with scalable neighborhood models from which we can track best practices.”

Support from Kresge has been crucial, Foster explains, because it validated Knowledge Quest’s approach to community development. It funded a 30-by-72-foot climate-controlled greenhouse, the hiring of a business manager and development of a master plan “to increase opportunities for the neighborhood through agriculture.”

The master plan foresees an expansion of the Green Leaf Learning Farm, construction of the Residences of Green Leaf, an apiary, street festivals and a park with an experiential playground.

“We are reinventing from within,” Foster says. “It’s about bringing back dignity and honor to people and neighborhoods.”

Fighting Blight and Leveraging City Assets

About 3 miles north, NPI President Steve Barlow is in a brainstorming session to plot next steps in the organization’s fight to rid the city of blight. During the past years, urban neighborhoods experienced epic out-migration of 170,000 people as the city’s land area grew from 208 to 323 square miles.

The dimensions of the problem are staggering: 30,000 vacant residential lots, 12,500 vacant houses and 2,500 vacant apartment units. Barlow’s methodical systems approach has attracted people from across the city to share in a framework for action.

“What we’ve been doing as a policy organization is to get a much better understanding of neighborhood housing and commercial markets that appear to have opportunities for revitalization and strengthening,” Barlow says.

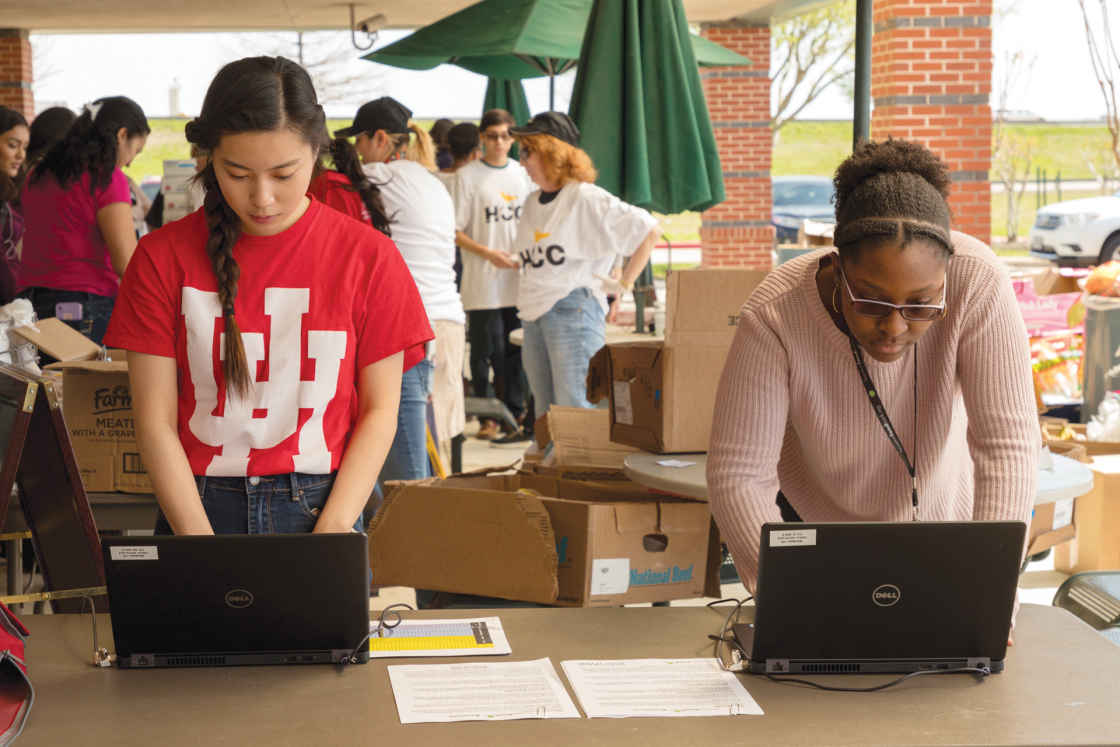

To that end, NPI’s work is built around four priorities: assembling data about blighted properties with the Memphis Policy Map that, for the first time, quantifies the problem in detail; community engagement so Memphians are essential partners in resolving blighted properties; reclaiming and reusing vacant land and abandoned houses; and improving code enforcement so there is a standard of property maintenance that is consistent.

Barlow’s appointment as NPI president stemmed from his work as a lawyer specializing in blight-related problems. He filed Memphis’ first lawsuit using a new Tennessee law, the Neighborhood Preservation Act. In 2012, he and business leaders formed NPI to act as the court-ordered receiver of blighted properties with absentee owners.

Charter for Change

A turning point elevated the work to a citywide priority in 2016, when NPI organized a summit that produced the interdisciplinary Memphis Neighborhood Blight Elimination Charter. It was the first time the city had a clear mandate: “Every neighborhood in Memphis and in Shelby County has the right to be free from the negative impacts and influences caused by vacant, abandoned and blighted properties.”

The 23-page charter became a call to arms for Memphis and created new momentum for change.

“We reached a point as a city where we had gotten so big and had so much empty land in so many neighborhoods that almost everybody understood that addressing blight was important to their quality of life, their home values, their kids staying here, the likelihood of business locating here and existing businesses staying here,” Barlow says.

Most of all, the charter became the umbrella under which each nonprofit working on blight issues could gather.

“Our goal was that the charter was the place where all ideas came together and was based on us staying connected, communicating and talking about what we were each doing and where to go first, and where it makes sense to intervene, where to stabilize, where to invest and where the market can be the market,” Barlow says. “We want to help strategic approaches get deployed as a result of neighborhood-based strategic thinking.

“It is about engaging with the community.”

Maximizing Opportunity

Barlow says Kresge has connected NPI to people and good practices around the U.S. He also took inspiration from a 2016 speech Kresge President and CEO Rip Rapson delivered in Memphis.

More than 100 butterfly sculptures installed in 2017 brighten the neighborhood around Carnes Community Garden in Memphis. “He said that we should be audacious in our goal setting,” Barlow recalls. “It inspired people to think big, and the opportunity by NPI to connect with Kresge has been formative to our growth.”

Kresge also influenced local thinking about blight and how to reimagine city assets such as Memphis’ riverfront, parks and other public places.

“We are looking at things defined as negative, and how they can be turned into positives and how to use data to make hard choices about where and how to spend money,” Barlow says. “We are thinking about systems and how we create neighborhoods of opportunity.”

Kresge’s Rush says the foundation’s focus in Memphis is to improve systems with “backbone infrastructure” like NPI, while supporting neighborhood-level community development such as Knowledge Quest. It’s turning out to be a powerful recipe for community development change in Memphis.

Share this story!

Why Equity Matters to Us

It’s the Driving Principle behind our Urban Opportunity FrameworkChair, Board of Trustees

Equity has been an important part of the conversation in The Kresge Foundation boardroom since I joined the board in 2004. As I look back, I find that as trustees we have not been outwardly vocal about equity, but it has indeed – in my recollection – always played a central role as we determine how best to fulfill our duties. All the while, foundation staff have gravitated with determination to address equity as a core principle and have demonstrated that in their fine work, day in and day out. As we consider the environment today in which federal, state and local policy decisions traced to race, gender, ethnicity and sexuality continue to deepen disparities in health, wealth, education and safety, I feel compelled to declare where our board stands and to discuss our work and how it matters.

Kresge’s focus and reach have completely transformed since I joined the board. For the 80 years following Sebastian S. Kresge’s generous mandate to “promote human progress,” the foundation issued capital challenge grants to help countless institutions and organizations across the U.S. build and expand their physical plants to serve public needs such as health care services, education and the arts. In the mid-2000s, we began using our resources in much more direct ways. Today’s work is incredibly complex and intricate, fully aimed at tearing down barriers and replacing them with enablers that increase opportunities for people to enter and thrive in the economic mainstream.

Although still firmly seeded in our founder’s mission, this new way of working forced our trustees — willingly — to establish a framework to ensure that each of the hundreds of unique grants and investments awarded by the foundation each year is keenly focused on an overarching goal.

As this strategy was taking shape, our reflections and deliberations were difficult: We knew the vision we sought would take time, involve risk and test every facet of the organization. Through much individual and group soul-searching, guided by our incredibly insightful President and CEO, Rip Rapson, the board adopted the “urban opportunity framework” as our north star. It was — and remains — rooted in the aspiration that American cities grow more inclusively so that disparities among their residents are eliminated and all have full access to the building blocks of just and equitable life opportunities. More simply: to expand opportunity for people with low incomes in America’s cities.

To consider our framework is to deal head-on with issues of equity. We constantly ask ourselves how we might demonstrate our commitment to help ensure that status at birth does not equal destiny. We ask how we might support our grantees as they confront bias and constraint. And we ask each other if we are truly advancing equity.

The lived experience of inequality in our country is well documented. Take, for example, practices such as redlining, which contributed significantly to persistent racial wealth gaps. Generations of African Americans seeking home ownership were blocked from receiving federally backed loans and experienced restricted neighborhood choice.

In Detroit, Cleveland, Baltimore, Philadelphia and countless cities across the country, African American families were prohibited from obtaining loans to improve their homes. They were also restricted from buying or building homes in flourishing communities while their white neighbors fled to newly built residences on spacious lots surrounded by schools with better resources and modern suburban shopping districts. A decade earlier, following Pearl Harbor, more than 100,000 Japanese Americans were held at internment camps based on unfounded fear that they were a risk to national security. These heinous actions, and thousands more, were intended to wall off entire populations. Acts of similar intent and spirit continue today.

Such patterns of inequality are abhorrent and self-defeating.

We are carefully confident that our urban opportunity framework is a strong

vehicle by which we can begin to address them, and I am extremely proud of

the examples you will read about in this report that demonstrate innovation

by cross-cutting issues at their root cause, including:

- “Connecting the Dots,” which brings to life an innovative partnership of data sharing among six health and human service providers, powering them to provide clients access to health care, housing, education, employment and other assistance in the same visit.

- “Food and Housing Insecurity – in College” describes the ways our Education and Human Services programs are collaborating to further student success by understanding and addressing student hunger and homelessness.

- “A Rising Tide of Climate Resilience” illustrates how climate-adaption and preparedness solutions are coming directly from residents most affected by climate-induced extreme weather — partly through Creative Placemaking activities — in New Orleans, a city on the front lines of a warming world.

Addressing systemic barriers to opportunity — deliberately and over the long term — is the challenge and objective of many fine philanthropic organizations that seek a more just and equitable society. We are a small part, but to us it is a crucial tenet of our responsibility, and it is unimaginable to do otherwise.

As trustees of this organization, we have been entrusted with an incredible sum and responsibility. Driving change in America’s cities is the strategic focus toward which we persevere. But at the very core of this work is the desire to confront the systemic inequality that pervades almost every corner of every community.

Fourteen years as a Kresge trustee have taught me that a strong and sustained focus on equity always has been — and must always be — a central measure of our success.

Welcome

We were delighted to welcome Kathy Ko Chin and Cecilia Muñoz to the Kresge Board of Trustees in 2017. In just a few months, Kathy, who serves as the president and CEO of the Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum, and Cecilia, who serves as vice president of Public Interest Technology and Local Initiatives at New America, have demonstrated their tight alignment to the foundation’s strategic direction. Both have made it their life’s work to find solutions to the most pressing challenges affecting our democracy and the people most impacted, and we are delighted that they have chosen to bring that perspective to Kresge’s work.